Opening

For much of its modern history, consulting has worked because effort has tracked closely with difficulty. As client problems grew more complex, firms responded by adding people, standardizing methods, and producing more detailed and heavier analysis. Larger teams and thicker deliverables followed naturally, increasing in step with the coordination, time, and expertise required to reach a credible answer. The amount of work required to reach an answer became a reasonable stand-in for both the complexity of the problem and the value of the advice rendered.

This will likely soon change. Artificial intelligence compresses the time and labor required to arrive at client-ready outputs. Drafts, analyses, and structured arguments can now appear almost instantly in forms that resemble finished deliverables. When production becomes abundant, time spent will stop functioning as a dependable proxy for usefulness, not because the underlying thinking has lost value, but because the effort required to produce credible work has been dramatically reduced.

This shift did not begin with artificial intelligence, but it accelerates sharply with it. Earlier waves of technology reduced mechanical work and pushed consultants toward interpretation and synthesis. Templates, analytical tools, and internal knowledge systems shortened cycles and standardized quality, but producing credible output still required enough time and coordination that effort remained a reasonable stand-in for value. Artificial intelligence will change this balance by placing deflationary pressure on the deliverables themselves. When a templated-output can be generated on demand, abundance replaces scarcity, and the physical artifacts of consulting will lose their ability to serve as a proxy for reasoning.

As production becomes easier, the basis on which advisory work is valued will begin to shift. Clients will gladly continue to pay for judgment, context, and the ability to distinguish signal-from-noise, but they will be less willing to pay for reconstruction, repetition, and the slow reassembly of insights that likely already exists in pieces somewhere inside a firm. As baseline analysis becomes easier to produce, continuity and retained understanding will matter more than the act of producing it. To say another way, the table-stakes to impress a client are shifting.

Frontier models can accelerate production, but only to the extent that they are given access to the problem they are meant to solve. Their usefulness depends on ingesting documents, responding to follow-up questions, and refining assumptions over multiple passes. Consulting firms have obvious client data protection protocols that limit this process. Much of the information that gives deliverables meaningful insights sit inside client contracts, internal analyses, draft positions, and partially-formed conclusions that cannot be sent to external servers without compromising basic obligations around confidentiality and control. As a result, frontier tools are most effective at the edges of an engagement. They can support early framing and generic research or novel exploration of new ideas, but the reasoning that shapes final conclusions must be either withheld or reconstructed in fragments.

Even if privacy constraints are surmountable, frontier models are not a perfect solution, sadly. Experience accumulates in fragmented ways across individuals, teams, and offices, resulting in the need for rework of insights that may already exist elsewhere inside a firm. As production costs fall and delivery speeds rise, client expectations will shift accordingly. Clients will increasingly expect firms to draw on existing accumulated house views and prior reasoning from across an organization, rather than reconstructing engagement-by-engagement.

That expectation will be difficult to meet using traditional operating models, and only partially addressable through the adoption of frontier tools alone. Firms that succeed in the AI era will be those that learn how to capture project-level context and reasoning and carry it forward safely, so it can be applied again without loss or exposure.

The competitive future of consulting will not be determined by who adopts artificial intelligence first, but by who organizes it coherently. Firms that lean heavily on frontier models will gain speed, but risk leaving their accumulated internal knowledge underused. Firms that preserve existing structures will protect client trust and confidentiality, but continue to rebuild context that may already exist within their walls. Resolving that imbalance requires treating speed and retention as separate problems rather than forcing them into a single stack. This concurrent parallel AI operating structure is the Two-Stack Firm

Section 1 — Origins and Craft

Consulting as we know it has many origin stories. One of the most instructive for our current contemplation comes from England’s early industrial revolution. By the 1840s, steam-powered mechanization allowed companies to grow at a scale that had not existed before, while also demanding unprecedented amounts of external capital to sustain that growth. As outside money became essential to fuel the growth of railroads and joint-stock companies, investors began to require an objective external assessment of financial and operational performance.

In 1849, The Great Western Railway depended on continued access to external capital to sustain its expansion, and probably operations, but investors wanted assurances that reported performance reflected reality. William Welch Deloitte, then only 25 and newly-established in practice, was appointed to examine the company’s accounts. Through the course of his review, he found that dividends were being paid out of capital rather than earnings (a major no-no), masking losses while presenting the appearance of profitability. When the practice came to light, several directors resigned.

The Deloitte story is important because of the role his young firm played, and less so for the accounting dirty laundry it found. He was brought in when internal assurances no longer satisfied investors, and his value came from being outside the organization rather than embedded within it. As similar situations arose, this role became repeatable. Firms trained practitioners to step into unfamiliar organizations, assess risk, and carry lessons from prior work with them. Records and procedures supported this process, but interpretation and decision-making remained tied to individual experience. As long as organizations were small enough, that model held. As scale increased, it became harder for understanding to move intact through people alone.

Section 2 — Scaling Up in the Gloden Era

The early consulting model held as long as client organizations could still be understood through concentrated human attention. Consultants were able to render judgment because experienced practitioners could see enough of a client’s operations to reason about them as a whole. As clients grew larger and more complex, that condition became harder to sustain. Information multiplied faster than it could be reviewed, and those responsible for governing these organizations became increasingly removed from day-to-day activity. The problem was no longer access to information, but the loss of a coherent view of how the organization actually functioned.

The profession responded by turning to systems. Early computing tools, including mainframes, punched cards, and structured data workflows, allowed information to be stored, reconciled, and revisited without depending on an individual’s memory. Work could be reviewed after the fact, compared across periods, and examined by people who had not been present when it was produced. This made oversight possible at a distance and reduced a firm’s reliance on personnel continuity. Judgment no longer had to live entirely inside the heads of experienced practitioners. It could be supported, checked, and repeated through shared records and standardized processes, even as organizations grew too large for any one person to fully grasp.

History sidebar: when computers and consultants first met

Joseph Glickauf joined Arthur Andersen in 1946 after serving as a Navy engineer during World War II. During the war he saw administrative work reorganize around machines because paper could not keep up. Joining Andersen, accounting still moved at the speed of ledgers, adding machines, and long nights of manual reconciliation. In the early 1950s, after seeing early computers such as the ENIAC and UNIVAC, Glickauf began bringing machines into accounting work that had never asked for them. They were expensive, awkward, required skills few people had, and were not obviously faster, which left senior partners openly skeptical. Glickauf pressed on with his prototypes and demonstrations. At one point he built a small binary counting device later called the Glickiac, and ran it in front of partners until the lights clearly outpaced anyone trying to follow along. This internal experiment eventually led to feasibility work for General Electric and later to large operational systems for Bank of America. By the mid-1950s, Glickauf made partner and became a pioneer in adopting computers in professional settings.

Consulting after computer adoption:

As consulting adopted computers, teams grew, which allowed critical thinking to move from execution and review, and in to process design. Teams began deciding in advance how data would be collected, reconciled, and reviewed, what counted as an exception, and when escalation was required. Those choices were embedded into processes, documentation, and eventually software, allowing work to flow through systems rather than relying on continuous senior oversight. This made further scale possible. Larger teams could be coordinated, deliverables made more consistent, and practitioners made more fungible across assignments without breaking the logic of the work. The model worked because the surrounding environment changed slowly enough for software and staffing to adapt without constant redesign. Once reliable outputs were established, firms could invest in standard methods and reuse them with confidence, combining decision-making with production and growing by increasing throughput. As firms grew, the slide deck and report became the practical unit of consulting work, because producing a substantial deliverable reliably signaled how much coordination, time, and expertise had been required to reach a conclusion. That condition held for decades, and likely would have held longer if not for artificial intelligence.

Section 3 — The Economics of Disappearing Scarcity

The modern consulting firm was built on an assumption that professional output was costly to produce and that its cost and volume served as a practical stand-in for value. Research, modeling, audit work, financial analysis, and structured argument required time, coordination, and specialized training. That difficulty justified both pricing and organizational design. Effort became the visible measure of worth because output was tangible and, generally speaking, difficult to fake.

This logic has failed before. Before the printing press, books were copied by hand, and the labor of reproduction made manuscripts scarce and therefore ultra valuable. Literacy was rare because access to text was expensive. Replication, not knowledge, was the bottleneck. When printing made copying cheap, books did not lose their meaning, but scribes lost their economic role. Value did not disappear, it just moved. Scarcity shifted from reproduction to authorship, editing, and interpretation. The mistake then and now is conflating production difficulty with intellectual value.

Modern consultants must now be careful to not occupy the position monasteries once did. Professional output remains expensive to an extent because it is slow and labor-intensive to produce, and because the people trained to do it are still scarce. Artificial intelligence will begin to reshape this understanding by reducing the time and labor required to generate drafts, analysis, structured arguments, and presentations. The economics are shifting in the same way they did when printing made reproduction cheap and scarcity moved elsewhere. Successful consultants will understand where the value is going, and will be ready to serve their clients in new ways.

Section 4 – Architecture of the Next Era

For many years consulting firms grew by adding people and standardizing the way those people worked. It has been an effective model. Large teams could apply well defined methods to familiar categories of problems, and clients could rely on consistent outcomes delivered at scale. That approach will eventually reach a limit. The issue is not the labor itself but the shared memory teams accumulate as they work, which functions as the firm’s real-time context window. This memory rarely moves beyond the group that created it, and it tends to disappear when those individuals disperse. A project file may preserve the final answer and even the steps that led to it, but it rarely captures the reasoning that created it. The debate behind an assumption, the bend in the logic, the moment a team realized a different path would produce a better result, all live in the minds of the people who were present. When they leave, the insight goes with them; sometimes to a competitor. When a new engagement begins, another group often repeats work that has already been done well elsewhere because they cannot access the thinking that shaped it. The teams keep churning, but memory continues to reset.

Frontier models can accelerate early project work by helping teams gather background information, but their usefulness ends where continuity begins. Each session starts as if the system has never encountered the firm’s circumstances before, which is effectively true. These models do not retain project history or institutional context, and they know no more about past engagements than a newly staffed analyst on their first Monday. Everything they require must be loaded into a finite context window, a temporary working memory that disappears when the session ends; or even before if it annoyingly fills mid-session. As a result, teams must continually reload prior analysis and the reasoning behind earlier decisions, only to watch that context vanish again. None of this externally-held context belongs to a firm, and none of it compounds over time.

Confidentiality introduces a further constraint. Frontier systems operate through external APIs, which means that analyzing client contracts, tax positions, or internal workpapers requires sending sensitive material beyond the firm’s control, a step no responsible practice can accept. These tools are valuable for speed and for early drafts, but they do not preserve institutional memory or accumulated judgment. They improve individual productivity without creating durable intelligence the next team can inherit.

The effects are most visible in large advisory engagements. For the sake of a thought experiment, let’s consider a global tax team helping a multinational company navigate a complex set of e-commerce-related filing obligations. A firm may have deep experience with similar issues, or even with peer companies in the same jurisdictions, yet that insight often fails to transfer intact between teams or offices to new work. In practice, fragments of judgment are scattered across geographies and practices. A lead partner may recall how the firm interpreted a ruling in Canada, while a manager remembers the logic behind a past structuring recommendation in Japan, but these pieces rarely assemble into a coherent client-ready view without meaningful manual intervention. Each group holds a partial understanding, and no one sees the whole. As a result, teams re-research regulations the firm already understands in pieces and reconstructs recommendation logic that has been built before. This repetition generates billable hours and quality work, but it reflects a structural inefficiency that becomes harder to justify as the macro cost of producing analysis continues to fall.

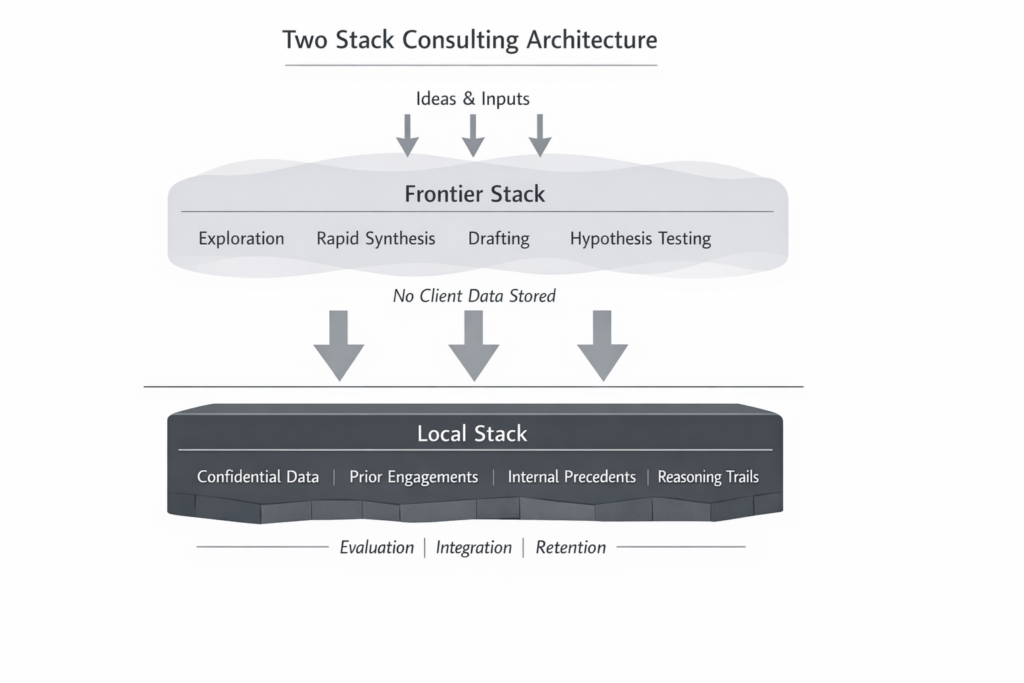

A two-stack architecture addresses this problem by separating what must remain private from what can be explored freely. The frontier stack contains external models that excel at broad research and rapid synthesis, but they do not retain project history, cannot hold confidential material, and do not carry institutional judgment forward. The local stack is built for that work. It runs inside the firm’s walls, persists across engagements, and becomes the project’s reasoning core, expanding its context window with each document, revision, and decision. Over time it sees more of the firm’s work than any individual ever could, and unlike individuals, it does not take its memory with it when it leaves. With this separation in place, firms can use frontier models for exploration without confusing speed with continuity or exposing sensitive material in the process.

The local stack begins with what the firm already knows. It reviews internal precedents, anonymized outputs from prior work, and stored statutes and regulations before any external inquiry is made. Only when internal knowledge reaches its limits does it query frontier models through the external stack, and any external material is human-reviewed before becoming part of the record. Drafts are assembled according to firm standards, and when an engagement closes, both the outputs and the reasoning behind them feed back into the system to compound growth. Confidential elements remain encrypted in segregated client records and can be retrieved later with full context, while deidentified, partner-approved insights can be retained in machine-readable files so future teams benefit without risking disclosure. In this way, judgment becomes durable rather than episodic, allowing intelligence to compound across projects while remaining firmly under human control.

By separating control from creativity, this structure keeps the local stack private and segmented by default. Teams access only the data they are authorized to see, and information flows inward rather than outward. Frontier systems never write directly to firm memory, and anything added to the local stack passes through human-review so that every change can be traced. Retrieval relies on the firm’s own data, which limits hallucinations and makes audits straightforward, since the system is recalling facts rather than improvisations. The result is a model that protects confidentiality while preserving the clarity required for professional judgment.

The frontier stack remains useful as a supportive tool, generating options, testing ideas, and synthesizing information at speed without touching client files or the firm’s core memory. It can broaden the search, but it does not carry the burden of being right. That responsibility stays with the firm, which is why the local stack becomes the real foundation. This foundation can then be audited or inherited for future use. At that point, growth comes less from adding people and more from retaining understanding. Put simply, a firm that separates what must be stable from what can be experimental is far more likely to keep both intact.

The Road Ahead

For most of the profession’s history, consulting work was shaped by the cost of producing it. Analysis required coordinated teams, sustained attention, and time measured in weeks, which meant that each additional question carried practical consequences for scope, staffing, and fees. Revisiting an issue was not simply an intellectual exercise, but a decision to reopen models, reassemble context, and extend an engagement’s duration. Those conditions structured how work unfolded and why it was packaged the way it was. The visible output of a project mattered because it reflected how much effort had been consumed in arriving at a conclusion. When analysis can be regenerated quickly and at low marginal cost, those constraints no longer govern how often questions are asked or how work progresses. Answers can be revisited repeatedly without reopening the surrounding work papers, and value begins to concentrate less in the act of producing work than in what persists across iterations.

The client-side consequence is not a loss of demand for advice, but a change in what clients are willing to accept as part of it. Decisions that are politically sensitive, legally exposed, or reputationally-charged still require human oversight, and clients will continue to value advisors who can interpret uncertainty and decide what matters among competing answers. What becomes harder to justify is starting from zero each time, reassembling context that was established in prior work and presenting it as newly discovered. As first-pass work becomes easier to obtain, the differentiator shifts toward whether an advisor can retain and apply what was learned before. Continuity begins to matter more than novelty, and the advantage accrues to firms that can carry understanding forward rather than repeatedly resetting it.

One response to this pressure is to accelerate deliverable production. External models can generate research, drafts, and structured analysis quickly, allowing teams to respond at a pace that would have been impractical before. On the surface, this appears to solve the problem, since iteration becomes easier and usable material arrives faster. What it does not solve however is continuity, because these systems operate outside the firm’s memory and do not retain understanding across engagements. The work they produce may be saved, but the reasoning that shaped it is recreated each time rather than carried forward. At the same time, fully exploiting these tools requires sending contracts, tax positions, and internal analyses beyond the firm’s control. The information that would need to persist in order for judgment to accumulate is often the same information that cannot safely leave a firm.

A different response is delay. Faced with unresolved questions around confidentiality, liability, and governance, many firms slowly work toward internal systems that better match their standards and client obligations. This is an understandable choice, and one that many leading advisory firms are actively pursuing, rather than adopting more costly or drastic changes. Although sensible in appearance, this approach does not actually alter how work is currently produced. Context is still rebuilt engagement-by-engagement, prior reasoning is reassembled rather than carried forward, and delivery continues to rely on the same labor-intensive processes that made consulting costly in the first place. As alternative approaches reduce the marginal cost of producing comparable analysis, firms that remain bound to repeated reconstruction absorb that cost each time work restarts. This choice may be prudent, but the economic position from which work is delivered may not always support it.

These responses point to the same constraint. Firms can speed up production, or they can maintain tight controls over sensitive material, but neither changes how judgment moves through the organization. Experience does accumulate, yet it remains embedded in people, local teams, and informal precedent rather than in systems that persist across engagements. A partner may carry a house view from one client to the next, but extending that understanding across offices, jurisdictions, or adjacent teams requires non-trivial effort, review, and coordination, often limited by confidentiality boundaries. Context exists, but it is costly to move. Each reuse demands revalidation, alignment, and careful handling of sensitive material. As production costs fall, that transfer cost becomes a dominant friction. Speed lowers the price of analysis, control preserves trust, but neither fully leverages the value that already exists within a firm’s walls.

What follows is not a tooling problem but a structural one. If in-house context is to compound rather than dissipate, it must be stored where it can persist, retrieved where it can be applied, and protected where it must remain private. Systems optimized only for speed exhaust their value once a draft is produced. Systems optimized only for control preserve trust but strand insight in place. The profession now faces a constraint it has not had to solve before. It must learn how to separate exploration from retention so that new analysis can be generated freely without erasing, leaking, or overwriting what the firm already knows. That separation is the precondition for scale in an environment where production is cheap and memory is not.

The only structure that satisfies these requirements is a split one. One layer is built for exploration. It uses large external models to search widely, test ideas, and generate possibilities at low cost, with the understanding that this work is transient, disposable, and non-confidential. The other layer is built for retention. It operates inside the firm, holds confidential material, and accumulates reasoning, decisions, and context over time. These layers serve different purposes and obey different constraints, and they cannot be collapsed into a single system without sacrificing either speed or trust. Together, they allow a firm to move quickly without discarding what it has already learned.

This architecture follows economic pressure rather than operational preference. As the cost of producing analysis continues to fall, advantage shifts toward firms that can retain and reuse what they learn without repeated reconstruction. Context compounds only when it can move forward intact across engagements and teams, rather than being reassembled each time under new constraints. Firms that develop this capability reduce the marginal cost of insight while increasing its consistency. Firms that do not remain dependent on rediscovery, drawing repeatedly on individual memory and local precedent rather than accumulated institutional understanding.

When analysis is cheap and continuity is not, firms that can retain and reuse judgment without slowing themselves down or violating trust will win. Some version of a Two-Stack architecture will be needed to remain viable at scale. Exploration and retention serve different purposes, operate under different constraints, and must be governed differently if either is to function well. Firms that deploy such a system will compound understanding and stop losing what they already know. In an environment where production is abundant, the ability to remember, carry forward, and apply context coherently becomes the defining asset.