Overview: What do Taylor Swift, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Adirondack chairs, cowboy hats, and the state of New Mexico have in common? If you guessed tuberculosis, you’re super cool, or we read the same books

Introduction

Before it was called tuberculosis, it was phthisis, tabes, scrofula or, more poetically, consumption. The disease has haunted our species since at least Neolithic times. DNA extracted from a 9,000-year-old skeleton in the Eastern Mediterranean shows clear signs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. It crossed oceans with early humans and was already flourishing in the Americas long before Columbus arrived; one of the few conditions to hold this distinction. A 700 AD mummified child from the Nazca culture in southern Peru bears lesions and bacilli consistent with tuberculosis. The samples come from an ancient civilization, but the disease artifacts would feel right at home in Victorian England. Researchers have similarly extracted the tell-tale chemical signatures of the infection from pre-colonial remains in Peru, Chile, Mississippi, and across Canada. For the inhabitants of those ancient settlements, tuberculosis was as familiar as fire. It thrived and traveled with us. It has been with us since likely our beginnings and lingers to this day as a leading cause of death worldwide.

Despite this long history, we now treat tuberculosis as a footnote. In the twenty-first century it still infects around ten million people each year and kills roughly 1.25 million, giving it the macabre distinction as the world’s deadliest infectious disease. Yet it is seldom mentioned outside public health circles or medical journals. Modern antibiotics, vaccines, and improved living conditions have pushed it to the margins of life in wealthy countries. If you are slacking at work and reading this in an air-conditioned office, you probably have more immediate concerns than coughing blood. But tuberculosis is our oldest enemy. It has shaped how we live, dress, build, and create, influencing fashion, music, architecture, and even the founding of cities and states. Its history is bound to ours, and despite our complacency, it has never truly been defeated.

Romanticizing Consumption: the fashionable affliction

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries tuberculosis became strangely glamorous. The disease had existed for millennia, but in an age obsessed with refinement and sensitivity, its visible effects were mistaken for elegance. Its pallor, thinness, and fever-bright eyes seemed to signal purity rather than decay. To the Romantic imagination, suffering was proof of depth. Charlotte Brontë even called it a “flattering” disease, and Lord Byron famously joked that dying of consumption would make him more appealing to the ladies. The very word consumption carried poetic weight, suggesting a soul burning too brightly; an artist literally consumed from the inside-out by their feeling. The “consumptive look,” with its narrow waist, flushed cheeks, and gentle cough, became not just a marker of beauty but a symbol of creative passion. Women cinched their corsets with whalebones until they could barely breathe, powdered their faces to perfect whiteness, and swallowed arsenic tonics (seriously, this was actually a thing) to imitate the glow of fever. Men cultivated beards to frame hollow cheeks and distant, poetic eyes. Painters and novelists filled their work with pale heroines and languid poets, equating frailty with beauty and disease with genius. The movie trope of a man gently coughing into a handkerchief, only to reveal a red stain, is as old as cinema itself, and its meaning to audiences has always been immediate.

This aesthetic preference hid grim realities. Consumption thrived in the damp air of tenements and the stale heat of factories, spreading fastest among the poorest. Yet by romanticizing the disease, polite society could admire the beauty of suffering without confronting the misery that produced it. Poets and composers did not choose tuberculosis; it chose them. John Keats, who once wandered the Lake District in search of inspiration, knew his fate the day he saw an “arterial blood bloom” on his handkerchief. As Frédéric Chopin’s strength faded, his compositions deepened. The works written in his final years, while losing his battle to consumption, are now among his most admired. In Taylor Swift’s song The Lakes, she sings, “take me to the lakes where all the poets went to die,” a reference to the same Lake District that once served as a refuge for consumptive Romantics like Keats and Wordsworth.

The Invention of Leisure: How Tuberculosis Shaped Travel

Long before antibiotics, doctors prescribed fresh air, sunshine, and rest. Health seekers boarded trains for the Adirondacks, Colorado’s high plains, New Mexico’s deserts, and California’s valleys. At the height of the Colorado rush, roughly one in three residents of the state were “consumptives” who had come to breathe mountain air. At the time, nearly a third of all deaths were from the same group. Colorado Springs, Denver, Boulder, and the aptly named Hygiene, sprouted hotels, sanatoriums, and tent colonies. Wealthy visitors reclined on wide verandas while poorer sufferers slept beneath canvas. Further west, the California towns of Pasadena and Altadena grew around hospitals like La Viña, where patients gardened, wove baskets, and watched sunsets from porches. It was a curious kind of boom; towns built not by mines or railroads, but by a disease.

In the Southwest, the cure craze took on a political dimension. Territorial officials in New Mexico wanted statehood but knew Congress viewed the region as too Hispanic and too Indigenous. Said another way, New Mexico reminded them too much of “old Mexico,” with whom the United States had fought a war only a few decades prior. To change perceptions, the territory launched a marketing campaign targeting “lungers” in the East with bold, medically-dubious claims that New Mexico had “the best climate for curing tuberculosis.” Pamphlets of the time boasted that the territory had the lowest death rate in America, and towns rebranded themselves as the Land of Sunshine. Thousands of affluent white patients bought property, opened businesses, and stayed. By 1912, the influx of health seekers was estimated at ten percent of the population. That was enough to ease Washington’s concerns, and New Mexico’s statehood application was approved.

Lightning round: Artifacts of Consumption’s Legacy

The Chair

High in the Adirondack Mountains, tuberculosis patients once spent their days swaddled in wool blankets, reclining on wide porches, and instructed to do little more than breathe. The “rest cure,” as doctors called it, prized stillness and fresh air above all else. Ordinary furniture proved useless for such long vigils, so a local carpenter designed a chair that could rest steadily on uneven ground, tilt back to ease the lungs, and cradle a blanket or book on its broad wooden arms. It became known as the Adirondack chair; a design for convalescence that later became the posture of vacation.

The Hat

In the 1860s, a young hatmaker named John was told what many consumptives heard: go west, breathe clean air, and hope for recovery. He left New Jersey in search of dry air and, upon reaching the frontier, noticed that the hats of the newly settled West kind of sucked. During the idle time of his convalescence, he made one of his own, built for the realities of life on the plains. It was broad enough to shield from rain and the punishing sun, and stiff enough to hold its shape against the prairie wind. When his health returned, he began to sell it, naming it after himself. With that, the Stetson and an indelible image of the American cowboy were born.

The Bullet

Without tuberculosis, the First World War might never have begun. In June 1914, a frail nineteen-year-old named Gavrilo Princip, coughing blood and convinced he would not live long, fired two shots at Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. The bullets killed the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and set in motion the chain of mobilizations that consumed and shaped the twentieth century. Those two shots became the butterfly effect that triggered two global conflagrations and reshaped the world order. Without the first war, there would have been no second. Without the second, the postwar world would look entirely different. One invalid changed everything with two bullets.

Princip’s sickness was more than background. Tuberculosis thrived in the impoverished Balkans where he grew up, leading to both physical decay and political resentment. He and his fellow conspirators often spoke of their illness as a form of martyrdom, proof that their bodies were already claimed by history. “There is no need to carry me to another prison. My life is already ebbing away. I suggest that you nail me to a cross and burn me alive.” he said at his trial.

Princip was sentenced to 20 years for his crime, but succumbed to tuberculosis shortly after his imprisonment. His body failed, but the contagion that he sparked reverberates to this day.

The Shift from Romance to Science

The romance of consumption ended in a laboratory. In 1882, Robert Koch stood before the Berlin Physiological Society and revealed a slide of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the tiny rod-shaped organism that had haunted humanity for millennia. With that single image, mystery gave way to mechanism. The consumptive was no longer the outward expression of an inner fire, but a carrier of contagion. Curtains were drawn back, floors scrubbed, and air declared the new medicine. Newspapers published diagrams of coughing lungs, and cities installed spittoons on every street corner.

The discovery remade more than medicine. It altered how people imagined virtue itself. Cleanliness replaced pallor as the sign of moral purity. The age of swooning and silk gave way to an age of soap and sunlight. The illness that had inspired Keats and Chopin became a matter of hygiene, ventilation, and germ control. Romanticism coughed its last, and modernity took a deep, disinfected breath.

The Miracle and the Forgetting

For centuries, tuberculosis shaped cities, fashion, and belief. Then, almost overnight, it seemed to vanish. In 1943, researchers at Rutgers University discovered streptomycin, the first antibiotic effective against the disease. Within a decade, once-fatal cases were cured, wards emptied, and the “white plague” that had haunted humanity since prehistory appeared to have been conquered by chemistry.

The victory felt absolute. Newspapers printed photos of patients rising from their beds, and public health campaigns declared the age of miracles. Doctors who once prescribed mountain air and bed rest now offered an injection, and later a pill. By the 1960s, public attention had moved on to nuclear brinkmanship, moon landings, and televised wars. It was the rarest of victories, one so complete that the world stopped remembering what it had been afraid of. The condition faded from headlines in the developed world, but it never disappeared, particularly in the developing.

Architecture of Recovery

Before modernism, comfort meant enclosure. Homes were layered with rugs, curtains, and carved wood, built for warmth and privacy. What once signaled comfort began to look like contagion. The same obsession that made frailty alluring now made cleanliness desirable.

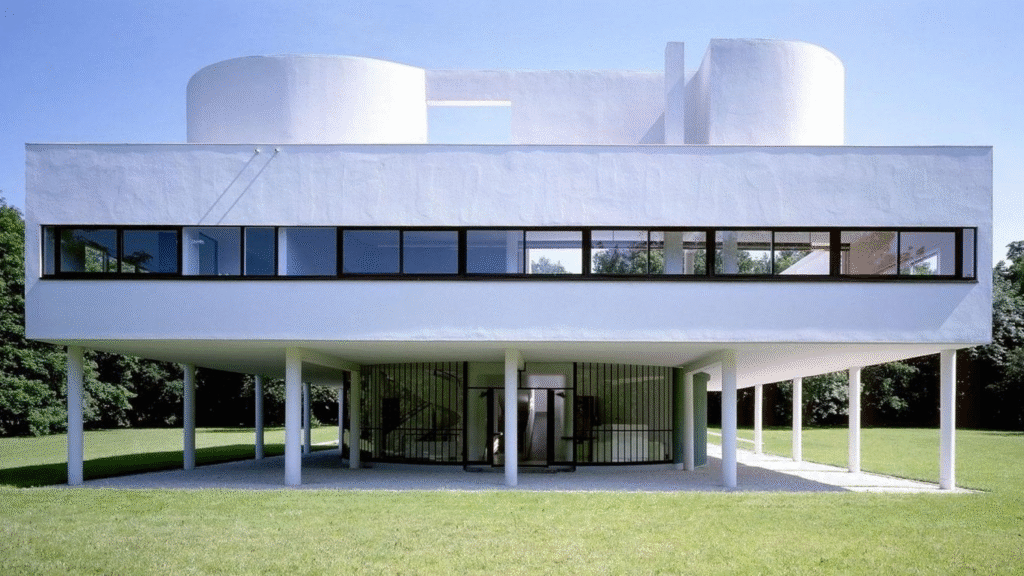

Sanatoriums appeared from the Alps to upstate New York, built as instruments of hygiene. Their white walls, tiled floors, and wide windows were meant to purify by exposure. Architects learned to think of sunlight as medicine and emptiness as order.

When the epidemic waned, the aesthetic remained. Le Corbusier’s white villas and Alvar Aalto’s glass-and-pine houses translated the architecture of recovery into everyday life. The cluttered parlor gave way to open plans and hard surfaces. Domestic space took its cues from the ward.

Modern architecture kept the vocabulary of healing and forgot the fear that produced it. The glass towers and minimalist rooms we inhabit today are descendants of those clinics. The world learned to admire the look of convalescence.

The Science and the Patient

In a small clinic outside Durban, a nurse unlocks a cabinet of orange pill bottles before sunrise. Patients line up quietly, waiting to swallow their morning dose. Each has carried the same ritual for months, some for years. The medicine is free, but the price is time.

Inside their lungs, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been playing a slow and patient game. Once inhaled, the bacterium hides inside the very immune cells meant to destroy it. The body responds by sealing off the infection within small nodules called tubercles. The air inside grows thin, the acidity rises, and the bacteria slow their metabolism almost to stillness. This can persist in a dormant state for decades, protected from both immunity and medicine.

This evolved clandestineness is what makes tuberculosis so difficult to cure. Most antibiotics work only when bacteria are dividing, but these divide slowly and unpredictably. A short course might kill the active infection while leaving the sleepers untouched. Treatment must therefore last long enough for every dormant cell to wake, and long enough for the drugs to reach them. The tubercles themselves are dense and poorly supplied with blood, making them difficult for medicine to penetrate.

The standard cure, known as RIPE, attacks the bacterium from several directions at once. Rifampicin blocks the copying of genetic code. Isoniazid disrupts the waxy armor of the cell wall. Pyrazinamide hunts semi-dormant cells hiding in the acidic core of tubercles, and Ethambutol stops survivors from rebuilding their walls. Together they form a six-month sequence: two months of all four drugs, followed by four months of rifampicin and isoniazid alone.

For most patients, the RIPE regimen works if it is completed as prescribed. Each pill must be taken on an empty stomach, often in the presence of a health worker. The side effects are harsh, and the schedule unrelenting. For vulnerable communities, six months of daily treatment is a long time to stay sick. Every clinic visit risks a lost wage or an empty table, and a missed dose introduces the risk of drug resistance.

When treatment lapses, the bacteria adapt. Drug-resistant tuberculosis now infects hundreds of thousands each year, often requiring two years of stronger and more toxic regimens. The newest among them, bedaquiline, was developed by Johnson & Johnson and hailed as a modern breakthrough, but pricing and patent control disputes delayed access in many of the countries where it was most needed. Modern medicine advances, but commercial realities still decide who is treated first.

Epilogue: The Enduring Foe

The age of sanatoriums ended, but the disease never did. It left the developed world for the heat of cities and slipped beneath the notice of those who could afford not to see it. What was once poetic in the past tense remains a leading cause of preventable death.

Each year, more than ten million people fall ill and over a million die. Almost all of those deaths occur in poorer countries, where treatment must contend with the more basic struggle to sustain daily life. The bacterium’s decline in the West was never a victory, only a shift in geography.

The vaccine that once promised control, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), was developed from a weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis in 1921. It still provides some protection to infants from the most severe forms of tuberculosis, though it likely no longer offers any meaningful defense for adults. In wealthier nations it has largely faded from memory. In poorer ones, it endures for no other reason than it is cheap, safe, and the only thing available. Better than nothing.

The disease has never truly disappeared, only drifted out of view for those in the West. Our short-sightedness, and the way it shapes therapeutic development and market priorities, remains tuberculosis’ best refuge. We have developed a kind of luxurious amnesia, forgetting an affliction that has existed for as long as we have.

My son, though American, was born in Saigon. Hours after his birth he received a small injection of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin. The vaccine leaves a faint, circular and raised scar that will mark him for life as someone born in the part of the world that cannot afford to forget phthisis.